No products in the cart.

A Most Rare Compendium

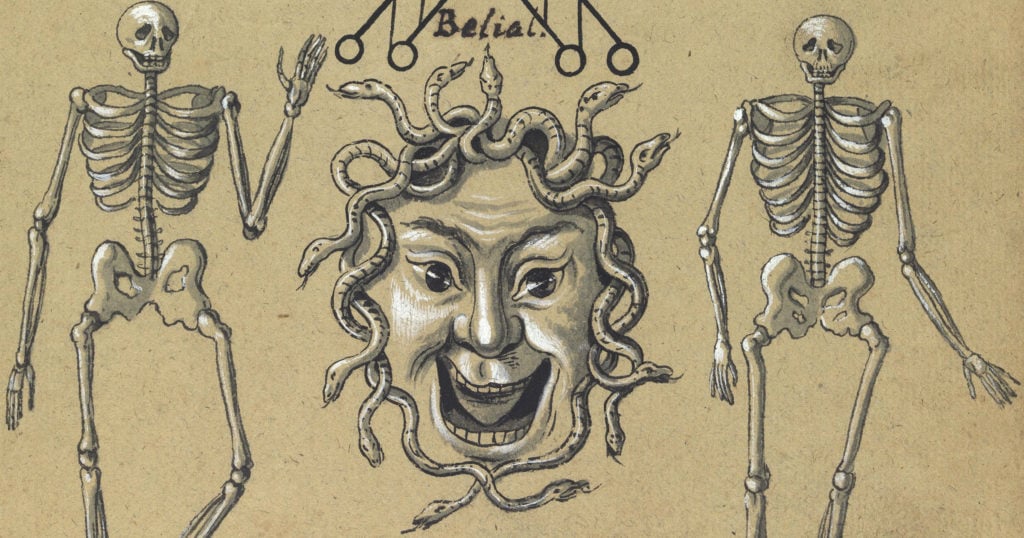

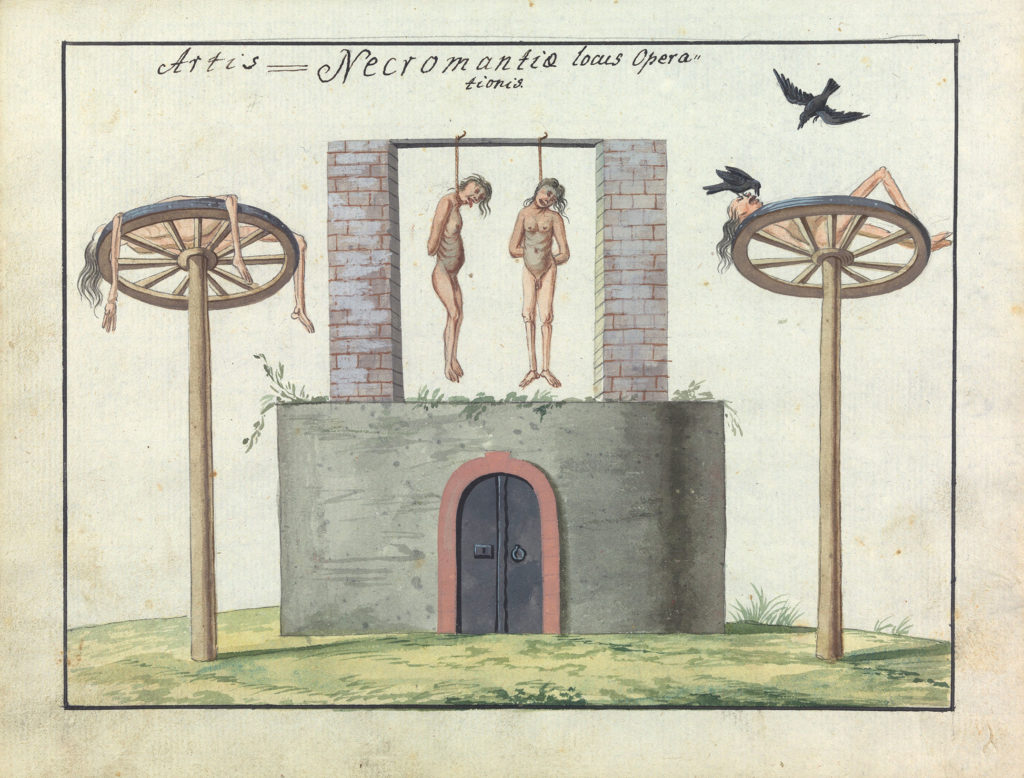

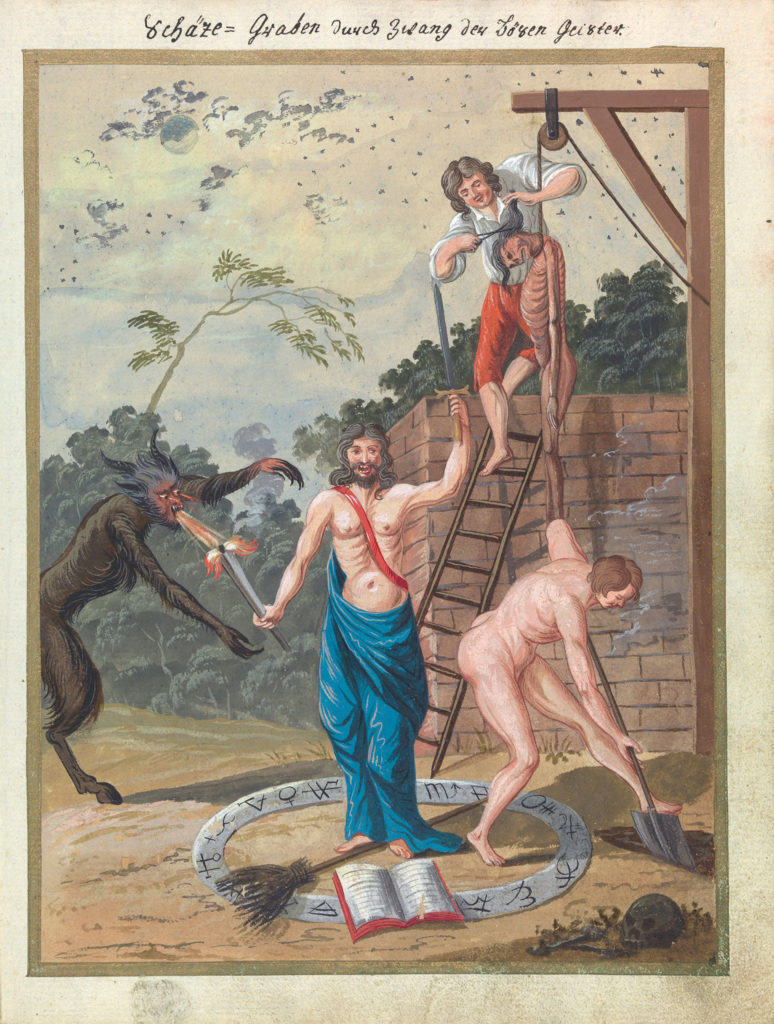

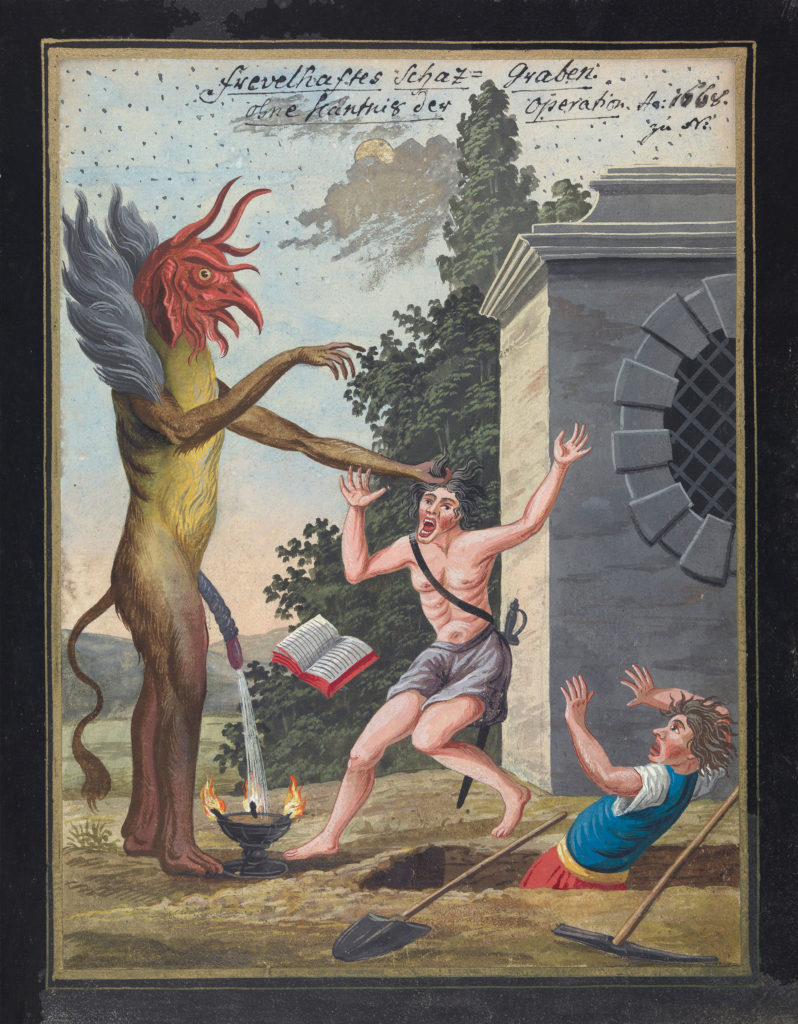

Compendium Rarissimum is the quintessential black magic grimoire, containing 31 Gothic illustrations of named demons, lesser evil spirits, rituals, tools and sigils. Inscribed in Latin and German, it provides instructions for signing a blood-pact with the Devil, the construction of a magic mirror, and the use of psychoactive plants to aid in summoning Hell’s denizens and bending them to your will. Its title page reads in full, “Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae sistematisatae per celeberrimos Artis hujus Magistros, Anno 1057. Noli me tangere,” or “Most rare Compendium of the entire Magical Art put together by the most famous Masters of this Art. Year 1057. Do not touch me.”

Textual references fix the actual date of the manuscript to no earlier than 1792. It is believed to be of Austrian origin, but there is there no record of it before 1928, when it was sold to London’s Wellcome Library by Viennese antiquarian bookseller V. A. Heck. After Wellcome released its digital collections on a Creative Commons license in 2014, the images were widely shared on blogs and social media. Fulgur Press followed up in 2017 with a translated facsimile edition, titled Touch Me Not.

Order Print

In the introduction to that book, Hereward Tilton explains that Compendium Rarissimum derives from a family of treasure hunting grimoires called Höllenzwang (“coercion of Hell”) that were exceedingly popular in the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648). Throughout the German states, treasure hidden from marauding armies lied buried and forgotten, and Höllenzwang texts furnished enterprising warlocks with the magical tools to enlist Satan’s legions in their quest for untold riches. The rituals demanded unwavering courage and painstaking attention to detail, for resentful demons would use all means at their disposal to break free and torment their summoner, yet in spite — or perhaps because — of the supernatural danger, magical treasure-hunting developed into a “fashionable crime” in 18th-century Austria. The ensuing craze further entwined magic and treasure in Germanic cultural memory.

Compendium Rarissimum was executed in both the style and materials of the Höllenzwang era, but is, in fact, a later embellishment of this tradition, designed less for practical use than to fascinate wealthy collectors. Indeed, the many of procedures outlined in the tome are anything but practical. Production of the magic mirror must take place between eleven o’clock and midnight, by a specified calendar, over a three year and eight month period. It requires dust made from gallows brick, a stirring rod of coffin wood, bronze from an altar bell, burial of the item at a gallows in a hanged man’s rags, as well as the cooperation of a bell-founder and an engraver. The bell-founder must work while devoutly reciting the Hail Mary and not look around should he hear a noise. The engraver must finish the final character under the gallows at exactly midnight. You, the aspiring necromancer, are instructed not to “allow yourself to become frightened…for the danger is great.”

Order Print

Tilton goes as far as to describe Compendium Rarissimum as a “work of supernatural horror,” rather than a genuine Höllenzwang, yet it draws upon magical traditions that were undoubtedly believed and practiced. It names a hierarchy of demons chiefly derived from The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin and contains excerpts from other magical texts familiar to scholars. And, like the Höllenzwang grimoires from which it derives, describes a system of folk magic in the form of psychoactive potions, salves and fumigations intended to “poison the imagination” and transport the practitioner “into a dream-world.”

Contact with each named demon required a specific fumigation. Belzebub: mandrake and human urine. Wamdial: dead man’s bones, asafetida and goat hair. Since many of the psychoactive plants available to Europeans belonged to the nightshade family, and these were often compounded with opiates, the risk of accidental overdose was significant. At the time Compendium Rarissimum was written, there were already well-known examples of treasure hunters dying this way. One can also imagine the type of drug experiences that credulous people must have been having in abandoned churches and lonely crossroads while attempting to summon Dagol, prince of darkness. “Depending on one’s constitution,” the compendium warns, these substances “can cause varying degrees of affliction, including paralysis, insanity and frenzy…The entire art of this secret consists in the correct proportion of the ingredients combined. Hence anyone unversed in the sorcerer’s lore should be wary of such magical operations.”

Order Print

Order Print

While the manuscript itself falls short of providing these specifics, it refers to a class of folk magician with detailed knowledge of their use, imploring the reader to “seek out a genuine master in this art who is able to teach you to prepare healing medicine from poison, and to tread on dragons and basilisks.” These witches, healers or shamans (however we choose to name them) would have possessed a body of knowledge that encompassed not only the proper collection and identification of psychoactive plants, but ways of compounding and administering them in order to mitigate their powerful toxic effects — knowledge that must have originally been gained through a generational process of investigation and experimentation.

What such traditions were active in Europe, and how widespread were they? Sources tell of a hallucinogenic ointment employed by witches to “fly” to their sabbats; of the benandanti, or “good walkers,” who left their bodies at night to do battle with the forces of evil. Clues are many, but answers are few. While practitioners of ceremonial or high magic left treatises and even manifestos for historians, there is little direct evidence of how so-called “cunning folk” might have been incorporating psychoactive substances into their practices, or what those who did actually believed about them. If Compendium Rarissimum is in one sense artifice — a “work of supernatural horror” — it is also a piece of this mystery, hinting at visionary folk traditions that, like so much treasure, lie buried and forgotten.

Image Gallery

Primary Sources

Touch Me Not: A Most Rare Compendium of the Whole Magical Art. c. 1792. Edited and Translated by Hereward Tilton and Merlin Cox, Fulgur, 2017.