No products in the cart.

Tonalist Figure Art by Thomas Wilmer Dewing

Thomas Wilmer Dewing was a coarse gent who produced highly refined images of elegant women. He had a large build, was prone to swearing, and could produce symphonies of tone and color to make the angels weep.

Dewing’s association with elegant women began in 1881 with his marriage to the still-life and portrait painter Maria Richards Oakley. The (soon-to-be) author of Beauty in Dress (1881) and Beauty in the Household (1882), Maria was an exponent of the Aesthetic Movement, which sought beauty in all things and for its own sake. She had an aphoristic speaking style and came from a patrician family that regarded their engagement as “something to cry over, & a personal loss to themselves,” but the couple shared a love of refinement and allegiance to art.

Through Maria, Thomas gained access to New York salon life. Together, they became founding members of an art colony in the upland meadows of Cornish, NH, where they wiled away their summers in a montage of fashionably beautiful moments. Dewing devoted himself to vegetable and flower gardening, planning elaborate dinner parties, twilight picnics and theatrical performances.

Order Print

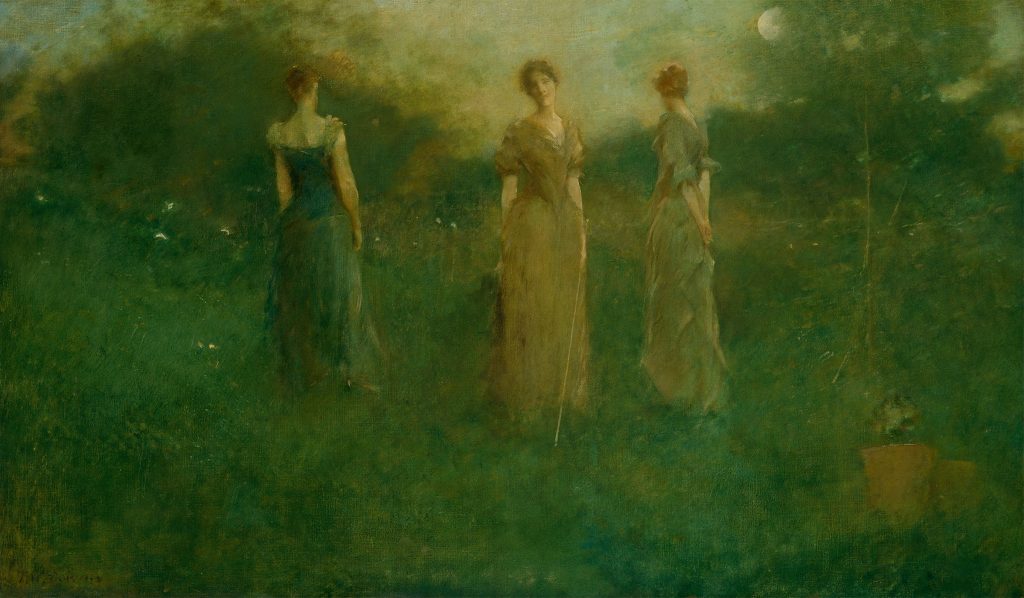

In the Garden (Spring Moonlight) is an example of the figurative landscapes he painted at Cornish. The composition is reminiscent of Botticelli’s Primavera and the Three Graces of antiquity, but the spirit is pre-Raphaelite. The physical and psychological distance between the models, their long, slender figures, and isolation from the hustle and bustle of modern life are characteristic of the Dewing style.

Thomas was a gifted painter, Maria a brilliant intellectual, and early works like these were very much a product of their collaboration. The problem was that he realized her vision so tragically well that she felt there was nothing left for her to say. In an 1888 letter to Ella Lamb, she described his works as “more mine in spirit than my own could ever be,” and in the final year of her life she would regret that “I have hardly touched any achievement…I dreamed of groups and figures in big landscapes & still I see them.”

Moreover, critics did not like it. They recognized the influences that Maria had recommended to Thomas and chided him for being derivative. Sadakichi Hartmann bemoaned the “pre-Raphaelite most” that obscured Dewing’s “true inner worth,” which he (rather impertinently) ascribed to “psychological influence at home.” Sadly for Maria, Thomas saw the need to separate himself from her influence.

Order Print

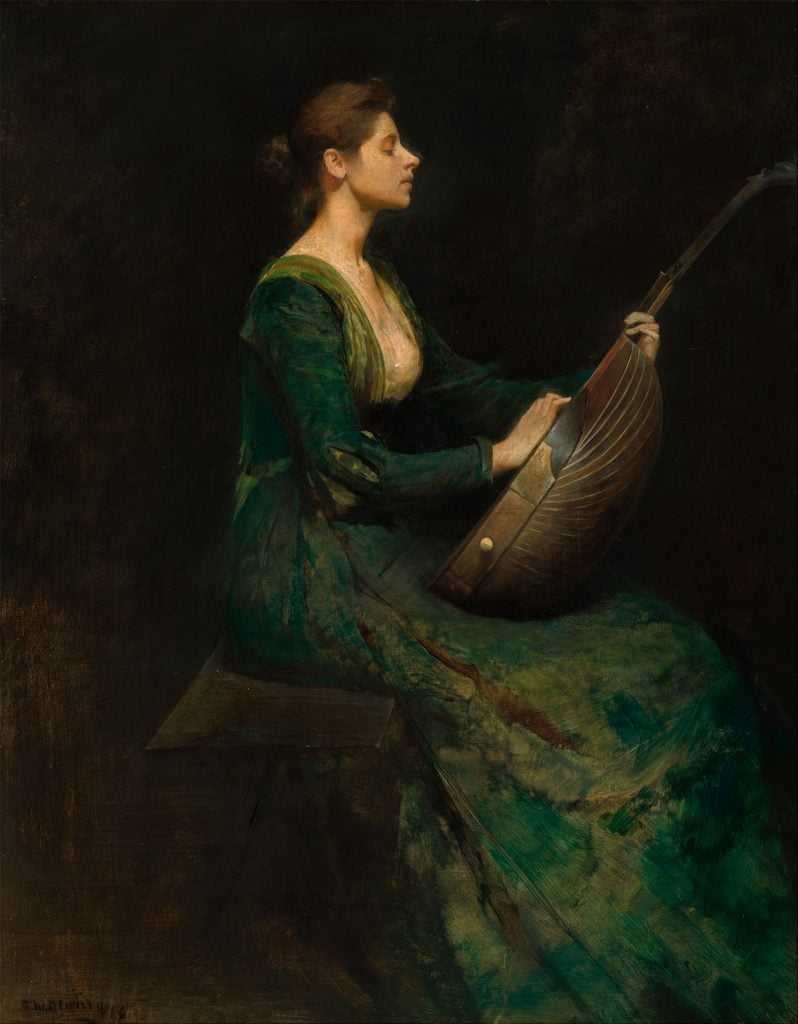

The figure of a lone musician on the cusp of inspiration was an appropriate subject for Dewing in a phase of his career when he was struggling to find his own voice. Lady with a Lute was the first expression of what was to become his signature subject: women seated in interiors, often with musical instruments, books or art objects. Audiences naturally viewed these works as aspirational; as exemplars of ideal womanhood, aristocratic leisure and sophistication. Hartmann wrote that Dewing’s models “help to improve our taste and manners, render our costumes and surroundings more picturesque, and our life softer and more agreeable, in one word more beautiful.” Dewing thought that Hartman should, “hang the educational value business altogether,” as “[w]e’ve heard enough of that kind of rot lately to last us for the rest of our natural lives.”

He believed, as James McNeill Whistler once stated, that “[a]s music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with the harmony of sound or color.” And, like Whistler, who infamously named a painting of his mother Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, he resisted efforts to read meaning into his work. He omitted any narrative, iconography, or clues as to his figures’ roles in society. As art historian Barbara Dayer Gallati points out, they “can neither be identified as wife, lover, mother, or sister nor conclusively be read as an allegory of love, beauty or nobility.”

Order Print

Lady in Gold and Lady with a Mask are both works that embody the tonalist muse he shared with Whistler. Susan A. Hobbs, who wrote the book on Dewing, cites Lady in Gold as an homage to Whistler’s Purple and Rose: The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks. She observes the orchid-color accent to the pervasive brown and gold color scheme, the contrasts of “the sitter’s relaxed, curved posture with the horizontal of the antique table,” and the “large and loosely woven brush-strokes” with passages where “the canvas is as finely wrought as an embroidery.” She quotes Frances Grimes, who noted of Dewing’s works that “all that was there…was treated as of supreme importance, floors and walls seen as beautiful and painted with the same consideration as the chiffons of the gowns.”

Order Print

Of Lady with a Mask, she writes:

“This painting incorporates the subtle spatial and atmospheric effects of a Vermeer with an up-to-date painterly execution. At the same time that he cast an elegant silvery hue across the canvas, Dewing lovingly caressed his composition with tiny strokes, meticulously and precisely establishing fine detail. He places miniscule points of color — green, turquoise, and pink, mixed with an occasional flash of red — like jewels throughout the gown. The careful application of these dots achieved an almost subliminal use of color; not stated obviously, it is nevertheless felt by the viewer. The handling of the face is an example of Dewing’s stippling technique at its finest. Flesh tones are flecked with orange, green, and red, while a dark glaze pervades the skin color on the shadowed side of the face. And, at this juncture in his career, Dewing introduced a new type of brushstroke into his work. It resembles a small quill in shape, which here runs throughout the sitter’s arm and gown while also defining the scroll on the wall. With these new techniques, Dewing maintained a uniform tonality in the work at the same time that he enlivened it with a sparkling vibration of color. In this he was in line with future painting developments, taking on problems that would engross Minimalist artists some fifty years later.”

Gallati, meanwhile, finds an ironic challenge in the sitter’s “questioning, almost unpleasant expression,” her tense, “pincerlike hold used to secure the mask,” and “the fact that her arm, rather than hanging limply at her side, is held slightly away from her body in a pose that requires tautness, not relaxation of muscle.” Her standoffish presentation scorns the spectator’s gaze, betraying Dewing’s impatience with audiences who could not see beyond the subject matter.

Dewing was elaborating a visual poetry that lied beyond representation, but because he continued working in a such a traditional idiom, few recognized him as a progressive artist, or appreciated his work beyond the surface level. In the end, his star would be eclipsed by the very modernism that his own work had so mutely anticipated.

Works by Dewing in Our Collection

Primary Sources

Hobbs, Susan A., and Barbara Dayer Gallati. The Art of Thomas Wilmer Dewing: Beauty Reconfigured. The Brooklyn Museum, 1996.